Lab-grown pork gets support from sorghum grain

Advertisement

Meat grown in a lab isn’t science fiction anymore. Cultured meats have existed for over a decade, and as of 2023, you might even find lab-grown chicken in restaurants (in the U.S., at least). Now, with the literal support of plant-based scaffolds, “clean meat” options are expanding. Researchers publishing in ACS’ Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry have created a prototype cultured pork using a new material: kafirin proteins isolated from red sorghum grain.

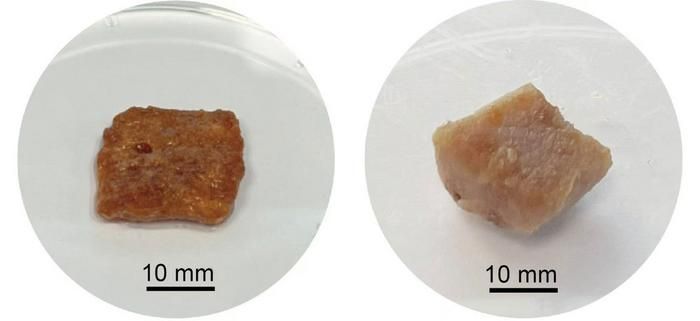

A prototype cultured pork (left) grown on a scaffold of red sorghum proteins appears similar to real pork (right).

Adapted from the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2024, DOI:10.1021/acs.jafc.4c06474

Cultured meats have emerged alongside plant-based meats as more ethical and environmentally friendly alternatives to eating animals. Manufacturing both types requires far less land and water, and the process emits fewer greenhouse gases during production. Unlike plant-based mimics, cultured meats use actual animal cells, but they are grown in a lab on porous protein scaffolds rather than obtained directly from an animal’s flesh. A variety of materials, including wheat gluten, pea protein and soy protein, have been used to create these supports. However, these water-soluble options require extra treatment steps or cause problems for those with gluten intolerances or allergies. To address that, Linzhi Jing, Dejian Huang and colleagues proposed using kafirin — a protein found in sorghum grain — as a gluten-free, water-insoluble alternative protein for scaffolding on which to grow a prototype cultured pork.

The team extracted kafirin from red sorghum flour and constructed a porous, 3D protein scaffold by soaking sugar cubes in the kafirin solution. The proteins stuck to the sugar crystals, which were then dissolved using water, leaving behind a cube-shaped support structure. To make the prototype cultured meat, Jing, Huang and colleagues introduced pork stem cells to the scaffold. After 12 days, they saw that the cells had readily attached to the kafirin and were differentiating into pork muscle and fat cells.

Compared to raw lean pork, the cultured pork contained more protein and saturated fat and fewer mono- and polyunsaturated fats. Researchers also found that red pigments from the sorghum provided the cultured meat with a pork-like color and some antioxidant properties. However, because the sorghum’s structural proteins were so stable, the cultured meat’s texture and color changed very little after boiling, making the raw and cooked versions look similar. The researchers say that additional work is needed to fine-tune the cultured pork’s nutritional and textural properties, but this study proves kafirin’s utility as a promising scaffold material for cultured meat products.

The authors acknowledge funding from the National University of Singapore (Suzhou) Research Institute Biomedical and Health Technology Platform and the Natural Science Youth Foundation of Jiangsu, China.