Child labour in the chocolate industry leaves a bitter aftertaste

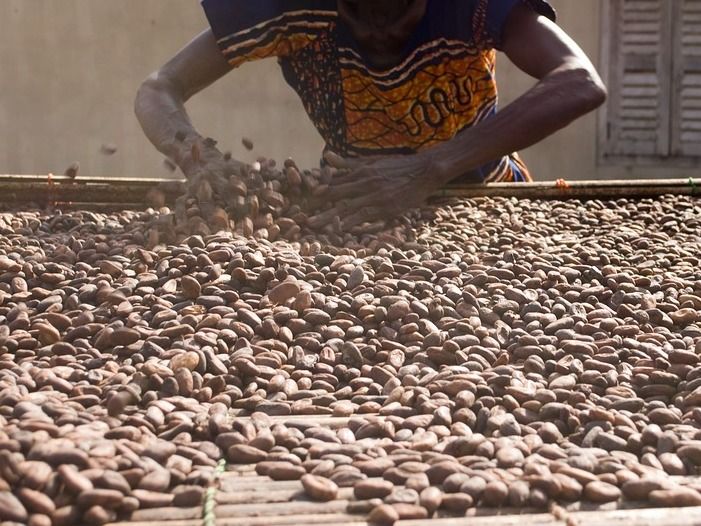

Much of the world's chocolate comes from Western Africa, where more and more children are working cocoa plantations. Chocolate manufacturers are acutely aware of the resulting image problem and some, like Nestle, are working to combat child labour in their supply chain. Getting results, however, remains difficult.

Nine-year-old Moahe used to spray weedkiller while working on her father's cocoa plantation. Morning and night, the frail girl also carried buckets of water, weighing more than she did, from the village well to her house.

Until recently, Moahe was one of around 2 million children labouring on cocoa farms in the Ivory Coast and Ghana, helping to produce the raw material for chocolate confections produced and sold in rich, developed countries.

"I didn't know that the work was something bad," Moahe says apologetically. "To me, it was normal."

But where child labour begins is the point where childhood ends; it endangers the child's health and adversely affects her or his education. Yet, due to a mixture of ignorance, tradition and poverty, child labour remains a common practice in many villages throughout western Africa.

About two-thirds of the world's cocoa production comes from the region, supplying raw materials for chocolate producers such as Hershey, Mars, Nestle, Ferrero and many more. Much of it will be consumed in rich countries during the coming Christian Christmas holiday.

The number of boys and girls working on cocoa plantations is currently rising. In the Ivory Coast, their numbers increased between 2009 and 2014 by some 50 per cent to 1.2 million, according to a US Labor Department-commissioned study by Tulane University in New Orleans. In Ghana, the number of child labourers dropped slightly during the same period, to 0.9 million.

In principle, child labour is forbidden in the Ivory Coast. Carrying heavy loads such as sacks of cocoa beans, the spraying of toxic chemicals such as insecticides or wielding machetes against weeds or to cut open cocoa pods are all against the law for children, as they are only officially permitted to do light work.

One of the organizations combating child labour on the ground is the International Cocoa Initiative (ICI). At the behest of Nestle, it has developed a system that has successfully prevented child labour in Konan Yaokro, as well as some 2,700 other villages.

The crux of the system comes down to having employees, such as Serge Alain Affian, working directly in the villages. The 30-year-old cocoa farmer visited every household in Konan Yaokro in order to determine how many people were living under one roof, what their occupations were and whether all the children were in school.

He then collected all the data from his talks with the locals and his visits to the plantations on his smartphone, and sent the information on to ICI.

"A child must be protected and belongs in school," Affian says, adding that he attempts to explain to locals why child labour is so wrong. Through his and other such efforts, ICI has already helped many former child workers such as Moahe.

In addition, some 1,400 classrooms have been built or renovated, and ICI also helps out with school tuition fees. To prevent smaller children from being taken along out to the fields, ICI has also set up kindergartens.

The cocoa harvested in Konan Yaokro goes, via a co-operative in the nearby town of N'Douci, to the US raw materials trading company Cargill, which in turn sells to Nestle.

The Swiss food giant, by its own account, buys some 47,000 tons of cocoa beans annually through the ICI system, or about 11 per cent of Nestle's worldwide cocoa purchases each year.

"No child labour is permitted in our supply chain," says Nestle's senior manager of social and environmental impact, Yann Wyss. The ICI system, which was first developed in 2012, must now be expanded to the point that all the cocoa purchased is free of child labour.

"The problem exists in our supply chain and we are taking this very seriously," Wyss adds.

In 2016, Nestle's candy sales totalled 8.7 billion Swiss francs (8.8 billion dollars). But in the battle against child labour and in the effort to build more schools, Nestle has thus far spent just 5.5 million francs.

Structural factors are also at play to make the fight against child labour in West Africa particularly difficult. Most cocoa farmers cultivate only a few hectares of land and can't afford to hire labourers, which leads them to turn to child workers.

Also, cocoa farmers are at the mercy of the forces on the world market. In 2014, a ton of cocoa fetched about 3,200 dollars; today, the price is only around 1,900 dollars.

While governments have intervened to ease the fluctuations, farmers were guaranteed a fixed price of around 1,900 dollars per ton last year. This has since dropped to around 1,300 dollars per ton this year.

"Nowadays, the effort is barely worth it," says cocoa farmer Attale Andre Yao.

And despite so many long days spent doing the hard manual labour that leads to the production of such a beloved treat, 9-year-old Moahe has only tasted chocolate once in her life.

"Really sweet," she says with a smile when asked how it tasted. But it was only once. In the end, hardly anyone in her village of 500 people can afford even a piece of chocolate. (dpa)