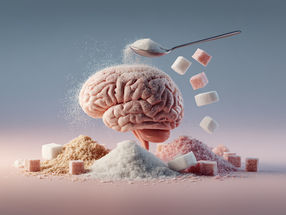

Short-term deficiency, lifelong consequences

War experiences can shape eating habits over generations, with women in particular overcompensating for the deprivation they have suffered - with health consequences.

Advertisement

War children, especially women, overcompensate for the lack of meat during the Second World War in Europe for the rest of their lives. Not only do they eat meat more often every day and spend more money on food, they also suffer more frequently from secondary diseases such as obesity or cancer than people who were not affected by meat shortages. Researchers from ZEW Mannheim, Erasmus University Rotterdam and the Global Labor Organization found this out in a study in which they evaluated data from around 13,000 people in Italy. Eating habits, body mass index and other health data from later in life were examined.

"Women in particular show lifelong effects; they consume more meat if they were affected by the lack of meat. And it is not only the war generation itself that tries to compensate for the deprivation suffered - their children adopt the behavior of their parents. So even a short-term deprivation in childhood has a major impact on the lifestyle and health of several generations," explains co-author Effrosyni Adamopoulou, PhD, researcher in the ZEW Research Group "Inequality and Distribution Policy".

Hunger widespread during the war

During the war, hunger was widespread in families of all socio-economic classes in Italy. This was partly due to the fact that many farm animals were slaughtered to meet the food needs of the invading armies, resulting in a significant reduction in the supply of meat. However, the fact that average per capita meat consumption had returned to pre-war levels in almost all regions of Italy by 1947 shows that the war only caused short-term meat shortages.

Sons preferred in wartime - girls suffer the consequences

The meat shortage during the Second World War had a significant impact on all those affected, especially the children of the war. However, sons were apparently favored over daughters when it came to distributing the scarce goods. The researchers found that between 1942 and 1944, girls lost more weight on average than boys in two-year-old children. The difference is even greater for working-class children: in rural areas, the average weight loss of working-class children between 1942 and 1944 was four percent for girls and only 1.4 percent for boys.

As the later women experienced the deprivation more severely, they are also more likely to suffer the health consequences of overcompensation. "Women who experienced greater meat deprivation in childhood tend to have a higher BMI and are more likely to be overweight later in life," explains Adamopoulou. "These women are also more likely to perceive their own health as poor and to develop cancer - this is consistent with medical evidence linking the consumption of red and processed meat to obesity and a higher risk of cancer."

The study is based on data from the Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT), including archival data on livestock numbers from the war years and historical slaughter figures, together with extensive survey data on eating habits and health outcomes at the individual level. Household wealth and income data also allow conclusions to be drawn about the effects on food expenditure.

Note: This article has been translated using a computer system without human intervention. LUMITOS offers these automatic translations to present a wider range of current news. Since this article has been translated with automatic translation, it is possible that it contains errors in vocabulary, syntax or grammar. The original article in German can be found here.