Digital ordering and food samples have unintended effects on consumer decisions

Advertisement

Today’s consumers have more options than ever in the food marketplace, both in terms of what they can buy and how they can make their selections. New Research co-authored by Annika Abell, assistant professor of marketing at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Haslam College of Business, investigates two aspects of food choice — digital ordering and food sampling — to learn how they affect consumer decisions.

Technology Leads to Less Mindful Decisions

Restaurants are increasingly offering customers digital ordering options such as kiosks, tablets and apps. These innovations reduce costs and allow restaurant staff to make quick changes to the menu. In one of her papers, Abell and her co-authors find that the presence of such technology also affects what consumers choose to eat and how much money they spend.

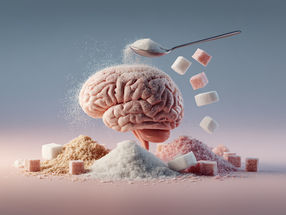

The use of digital ordering technology activates a less thoughtful, more automatic decision-making process, the researchers say. Less cognitive involvement leads consumers to make indulgent choices in terms of both unhealthier food orders and higher overall spending.

“With devices, it’s about instant gratification,” Abell says. “People quickly focus on the option they really want, which is more likely going to be the burger than the salad for the average person. When people order face-to-face or from a paper menu, they take a little longer to think it through and are more likely to switch to a healthier option.”

Abell notes that the effect is more pronounced with younger, more tech-savvy customers, and that time of day also affects digital ordering. “People seem to be in a little bit healthier mindset for lunch than for dinner,” she says. “They’re more cognitively depleted at the end of the day, and more likely to choose unhealthy options.”

The findings suggest that fast-food outlets and other establishments that sell indulgent foods would benefit from making digital ordering modes available. For restaurants that are associated with healthier foods, non-digital ordering modes would be more effective. Those that have a wider range of menu items might harness technology to increase profit while also offering their customers more nutritious choices.

“If you’re a restaurant like a fast-food chain that also has healthy options, maybe those bring you more money because they are more expensive,” Abell says. “Kiosks give you the opportunity to push healthier additional items like a side salad that you can upsell on a device very quickly.”

As digital ordering options become more prevalent and take on new forms, Abell says consumers and policymakers need to be mindful about how such innovations can affect decision making. “We adopt these things very quickly,” she says. “It’s very easy to fall into this convenience, but we need awareness that we may make different choices when we consistently use these devices.”

Pairing Samples with Purchases

In a separate paper, Abell and her co-authors examine the widespread practice of food sampling at retail stores and restaurants. The team investigates how consuming food samples can have unintended effects on customers’ subsequent purchases of other food items.

Depending on the store or restaurant and its marketing goals, food samples can vary widely in nutritional value. A well-established paradox, known as the licensing effect, has shown that sampling an item that a consumer perceives to be relatively nutritious tends to result in greater purchases of less nutritious foods. This effect happens when a person makes a more nutritious choice and then feels as if they have permission to make subsequent indulgent choices as a kind of reward.

Abell and company break new ground in licensing effect research by studying similarities and dissimilarities between the sampled item and the ensuing purchases. They find that consumers are more likely to fall into the licensing effect pattern when they perceive subsequent options to be significantly different from the sample. On the other hand, if someone thinks the subsequent options are relatively similar to the sample, they tend to want more of what they initially sampled.

Abell says, “If I sample a piece of chocolate at Costco and then I go into the frozen food aisle and see completely dissimilar things, versus walking straight to the candy aisle where it’s relatively similar, the small sample can influence the type of purchases I make, depending on what I see next.”

This holds true whether the initial sample was something the consumer perceived as more nutritious or less nutritious. “Whether we give people a little piece of chocolate or a freeze-dried strawberry, if they can choose to have more of the same item, they want more of the same,” Abell says.

“Food and technology: Using Digital Devices for Restaurant Orders Leads to Indulgent Outcomes,” co-authored by Abell, Dipayan Biswas and Christian Arroyo Mera (both from the University of South Florida), and “Effects of Sampling Healthy Versus Unhealthy Foods on Subsequent Food Purchases,” co-authored by Abell, Biswas, J. Jeffrey Inman (University of Pittsburgh), Johanna Held (industry) and Mikyoung Lim (University of South Florida), have been published by the Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science.