Kid Influencers Are Promoting Junk Food Brands on YouTube—Garnering More Than a Billion Views

Little-known but common form of product placement boosts children’s exposure to unhealthy food, warrants stronger regulations

Kids with wildly popular YouTube channels are frequently promoting unhealthy food and drinks in their videos, warn researchers at NYU School of Global Public Health and NYU Grossman School of Medicine in a new study published in the journal Pediatrics.

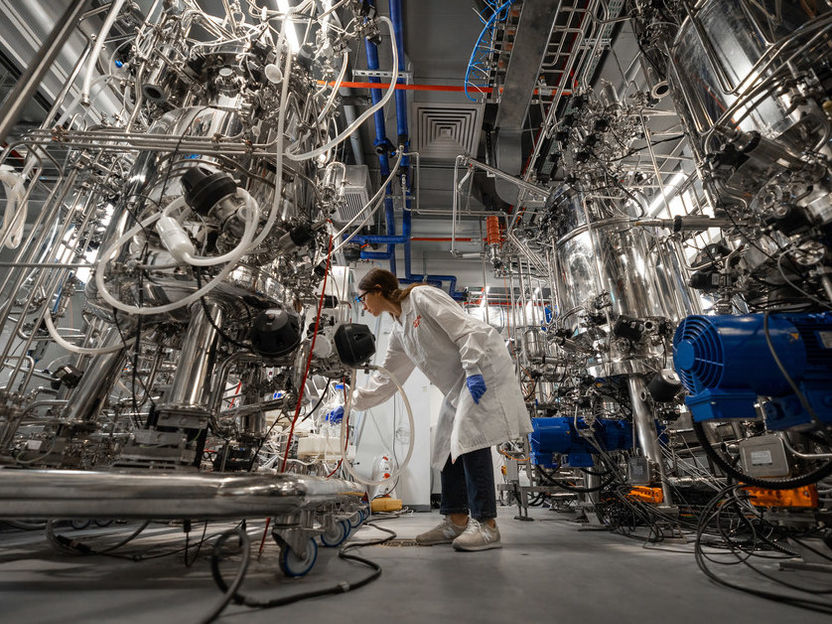

Photo by Patricia Prudente on Unsplash

Food and beverage companies spend $1.8 billion dollars a year marketing their products to young people. Although television advertising is a major source of food marketing, companies have dramatically increased online advertising in response to consumers’ growing social media use.

“Kids already see several thousand food commercials on television every year, and adding these YouTube videos on top of it may make it even more difficult for parents and children to maintain a healthy diet,” said Marie Bragg, assistant professor of public health nutrition at NYU School of Global Public Health and assistant professor in the Department of Population Health at NYU Langone. “We need a digital media environment that supports healthy eating instead of discouraging it.”

YouTube is the second most visited website in the world and is a popular destination for kids seeking entertainment. More than 80 percent of parents with a child younger than 12 years old allow their child to watch YouTube, and 35 percent of parents report that their kid watches YouTube regularly.

“The allure of YouTube may be especially strong in 2020 as many parents are working remotely and have to juggle the challenging task of having young kids at home because of COVID-19,” said Bragg, the study’s senior author.

When finding videos for young children to watch, millions of parents turn to videos of “kid influencers,” or children whose parents film them doing activities such as science experiments, playing with toys, or celebrating their birthdays. The growing popularity of these YouTube videos have caught the attention of companies, who advertise or sponsor posts to promote their products before or during videos. In fact, the highest-paid YouTube influencer of the past two years was an 8-year-old who earned $26 million last year.

“Parents may not realize that kid influencers are often paid by food companies to promote unhealthy food and beverages in their videos. Our study is the first to quantify the extent to which junk food product placements appear in YouTube videos from kid influencers,” said Bragg.

Bragg and her colleagues identified the five most popular kid influencers on YouTube of 2019—whose ages ranged from 3 to 14 years old—and analyzed their most-watched videos. Focusing on a sample of 418 YouTube videos, they recorded whether food or drinks were shown in the videos, what items and brands were shown, and assessed their nutritional quality.

The researchers found that nearly half of the most-popular videos from kid influencers (42.8 percent) promoted food and drinks. More than 90 percent of the products shown were unhealthy branded food, drinks, or fast food toys, with fast food as the most frequently featured junk food, followed by candy and soda. Only a few videos featured unhealthy unbranded items like hot dogs (4 percent), healthy unbranded items like fruit (3 percent), and healthy branded items like yogurt brands (2 percent).

The videos featuring junk food product placements were viewed more than 1 billion times—a staggering level of exposure for food and beverage companies.

“It was concerning to see that kid influencers are promoting a high volume of junk food in their YouTube videos, and that those videos are generating enormous amounts of screen time for these unhealthy products,” said Bragg.

While the researchers do not know which food and drink product placements were paid endorsements, they find these videos problematic for public health because they enable food companies to directly—but subtly—promote unhealthy foods to young children and their parents.

“It’s a perfect storm for encouraging poor nutrition—research shows that people trust influencers because they appear to be ‘everyday people,’ and when you see these kid influencers eating certain foods, it doesn’t necessarily look like advertising. But it is advertising, and numerous studies have shown that children who see food ads consume more calories than children who see non-food ads, which is why the National Academy of Medicine and World Health Organization identify food marketing as a major driver of childhood obesity,” said Bragg.

The researchers encourage federal and state regulators to strengthen and enforce regulations of junk food advertising by kid influencers.

“We hope that the results of this study encourage the Federal Trade Commission and state attorneys general to focus on this issue and identify strategies to protect children and public health,” said study co-author Jennifer Pomeranz, assistant professor of public health policy and management at NYU School of Global Public Health.

In addition to Bragg and Pomeranz, study authors include Amaal Alruwaily, Chelsea Mangold, Tenay Greene, Josh Arshonsky, and Omni Cassidy of NYU Langone. The research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (DP5OD021373-05) and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1T32HS026120-01).