Chocolate remains bitter for farmers

Whether it's Santa Claus, a chocolate wreath or simply a bar: chocolate sweetens Christmas for many people and is a comfort for many, especially during the pandemic.

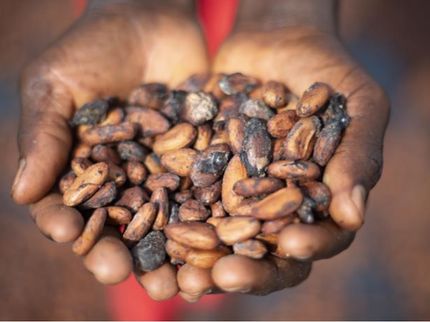

Bild von David Greenwood-Haigh auf Pixabay

After a small slump at the beginning of the pandemic, production and sales rose again last year. In contrast, the reality for cocoa farmers remains bitter.

Every year, chocolate products are sold worldwide for an estimated 122 billion euros. Farmers get about 7.3 percent of that and earn less and less. In October, the price of cocoa fell 18.5 percent in West Africa. To make a living, it should actually be 50 percent higher.

Prices will continue to fall and poverty will increase, predicts the "Cacao Barometer," the trend report by the Federation of Non-Governmental Organizations and Trade Unions in the Cocoa Market, based in the Netherlands. Amsterdam has the world's largest cocoa port: about 25 percent of the world's production is handled here.

For 20 years, a lot has been done internationally to improve the situation of farmers and to combat deforestation and child labour. There are quality labels, certificates, Fairtrade producers and, in several countries, cocoa platforms that advocate sustainable production. With little success.

"The conventional aid programs don't help," researcher Yuca Waarts of Wageningen Agricultural University tells Deutsche Presse-Agentur. She is the author of a new study on cocoa farmers' incomes. More than 60 percent of the total cocoa production of almost 5 million tons a year comes from the West African countries of Ghana and Ivory Coast. Yet 75 percent of cocoa farmers in these countries do not earn a living wage. That means not enough for food, housing, education and health.

In the past 30 years, cocoa production has more than doubled. Overproduction, Waarts says, has driven down prices and incomes. But just raising prices won't help, her study found. The governments of Côte d'Ivoire and Ghana already pay farmers a supplement to secure their incomes. But that is not enough. Even if prices were doubled, only about 41 percent of farmers would earn enough to send their children to school, for example, rather than to the cocoa fields. That's because many farmers have fields that are too small and yield too little, Waarts says.

Faitrade producers do pay their farmers a fair price. But that only helps those who have enough acreage. And the Fairtrade share of world trade is still small. In Germany, it is about 17 percent.

"Raising the market price is only part of the solution," says Waarts. The market needs to be regulated, he adds. The example of oil production is obvious. So a kind of cocoa opec, where production and price are regulated. The areas under cultivation would have to be large enough, and there would have to be a social safety net.

Amsterdam-based chocolate producer Tony's Chocolonely has catapulted to the top of the Dutch market with its message of fair trade and slave-free chocolate, and is number two with about 17 percent of the market. The Fairtrade company pays its 9,000 or so farmers between 30 and 40 percent more than conventional traders. "Seventy-two percent of our farmers in Ghana have come out of poverty this way," says the company's Belinda Borck. The manufacturer also said it found only 3.9 percent child labor among its own farmers. In conventional trade, the figure is 50 percent. The company also only trades with cooperatives, which strengthen the productivity of individual farmers.

Tony's wants to turn the international market around and is also relying on German partnerships in its "open supply chain." Wholesalers such as the Aldi supermarket chain, the Jokolade company or the Dutch producer Delicata and the Albert Heijn supermarket chain already buy beans at a fair price.

So far, this is also paying off for the Amsterdam-based company. In 2020, sales were well over 100 million euros for the first time, 24 percent more than in the previous year./ab/DP/stk (dpa)

Note: This article has been translated using a computer system without human intervention. LUMITOS offers these automatic translations to present a wider range of current news. Since this article has been translated with automatic translation, it is possible that it contains errors in vocabulary, syntax or grammar. The original article in German can be found here.